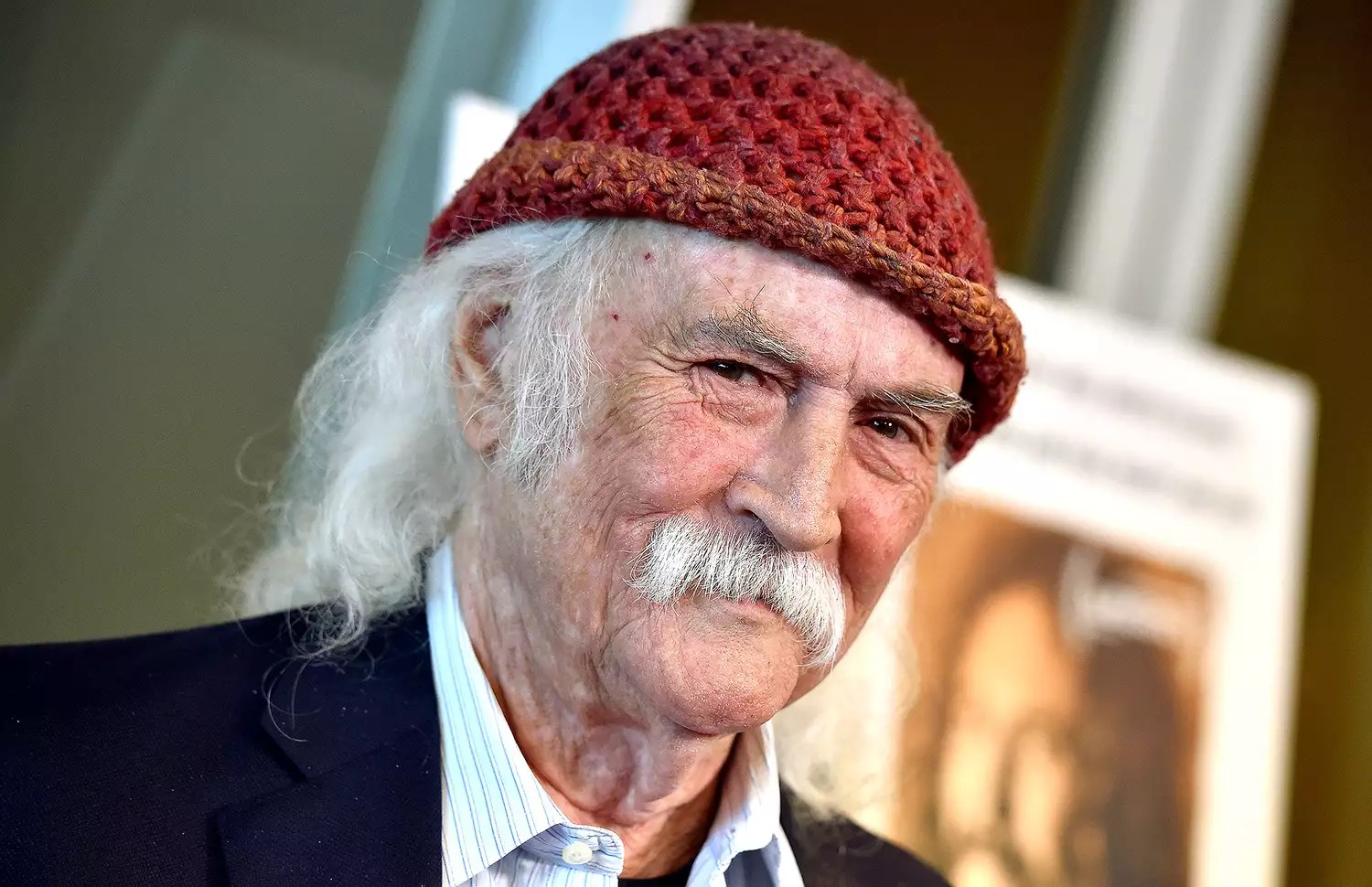

Photo: Axelle/Bauer-Griffin/FilmMagic

With time on his hands, he traveled to Miami, where he’d played as a penniless folkie years before. There he encountered two ladies who would have a major impact on his life. The first was a 74-foot mahogany sailboat,The Mayan, which became both a personal touchstone for health and freedom, and a muse for beloved songs like “Wooden Ships,” “The Lee Shore,” “Page 43” and “Carry Me.” The second was a young Canadian singer named Joni Mitchell. Enchanted after watching her perform in a Coconut Grove coffee house, he persuaded her to return with him to L.A. where he integrated her into the local music community and helped her secure a record deal. His admiration for her talent remains undiminished after half a century. “She’s the best there is,” he says with touching affection. “There’s no question. She’s better than all the rest of us.”

Their self-titled debut album shot to the top of the charts in the summer of 1969, and they hadn’t even played a concert together. To help tackle their complex arrangements live, the trio recruited Stills’ former Buffalo Springfield bandmate Neil Young, and their name was appropriately amended. Their second-ever gig took place at the Woodstock festival, where Stills famously told the crowd that they were “scared s—less.” It wasn’t so much the sea of people stretched before them that rattled the nerves, but the small circle of musical peers like Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Grace Slick and the Band watching expectantly in the wings to see if the so-called supergroup could deliver the goods.

“A girl — pretty girl — tan, blonde, is walking in the mud. Cuts her foot. Glass in the mud. Bad cut, bleeding. She’s hurt. She’s standing like a stork on one leg, holding her foot. Bleeding bad. A policeman just came on duty: sharp crease in his pants, mirror-shined shoes. Beautiful. This guy could be a recruiting poster. He sees the girl. Immediately, without hesitation, he walks into the mud with the shiny shoes. Gets the mud and the blood all over himself, all over his brand new shiny uniform. Picks the girl up, carries her gently and nicely, obviously being careful and nice with her. He carries her to his car, lays her in his back seat very carefully and gently. He’s obviously a gentleman. He’s obviously a nice cat. He lays her in there and gets ready, and his car’s stuck in the mud. Fourteen hippies pushed that car out of the mud. And I said, ‘Okay. This is it. This is working. This is what I wanted to see. This is how it’s supposed to work.’ That’s my Woodstock story. I saw it with my own eyes. There was a moment where we had hope. We saw how it could be better — plainly, obviously, right there in front of us. And we said, ‘Ah, that’s what I’m looking for. I don’t want a war. I want this.’ And that’s what Woodstock was. That’s why it’s stuck in everybody’s head: because, for a minute, we hoped.”

He spent that Christmas in a Texas prison, detoxing without so much as an aspirin. As he grew stronger, he confronted his past. “I woke up in a cell in Texas and remembered who I am,” he says. “I started fooling around with the guitar out in this little cinder block room and my brain started to work again.” Slowly, the future came into focus. He started playing with the prison band and eventually began writing. He cites one song, “Compass,” with obvious pride as “the first good song that I wrote” after getting clean. The lyrics detail the years he spent adrift, before offering a message of hope for himself.

I have wasted ten years in a blind-foldTen-fold more than I’ve invested now in sightI have traveled beveled mirrors in a fly crawlLosing the reflection of a fightBut like a compass seeking NorthThere lives in me a still sure spirit partClouds of doubt are cut asunderBy the lightning and the thunderShining from the compass of my heart

The compass had guided him back to music. “Having almost lost it, I treasured it more. I’ve been much more faithful to it since. When I didn’t die, and I didn’t end, I got a new chance. I felt much more strongly that I have to be true to my purpose here.” Within days of his release on Aug. 8, 1986, he appeared onstage with Nash, marking his first sober performance in two decades. He had just celebrated his 45th birthday.

Though he’s grateful to be singing, finances have forced him to part ways with another great love:The Mayan. It’s a personal loss he resolutely blames on the payment practices of streaming services. “I had the boat for 50 years. I sailed it all over the world. I loved it more than any other physical object on this planet. I had to sell it because they don’t pay me for records anymore. Imagine you worked your job for a month and they paid you a nickel. It’s completely out of proportion wrong.”

Regrets, he’s had a few; his biggest being the time lost to addiction. “It cost me probably 10 years of my life. I regret it greatly. If I had to change one thing, that would be it. No hard drugs, because it nearly killed me and put me in prison and, most importantly, it kept me from making music.” Intended or not, his recent geyser of work is a throw-down — a signal to his CSNY brethren that he’s back and means business, and a challenge to artists a quarter of his age to stand up and be counted. “I’ve wasted so much time and it grates on my nerves. I’m obviously trying really hard to do a whole s—load better. I’m trying really hard to be a decent human being and I certainly am doing what I was put here to do, which is make good music.”

source: people.com